Notwithstanding China’s civil law tradition, China’s use of anti-suit injunctions (ASI’s) in FRAND disputes has begun to be selected for adoption into the body of “typical cases” 典型案例 that may be referred to by Chinese IP judges when encountering cases with similar fact patterns.

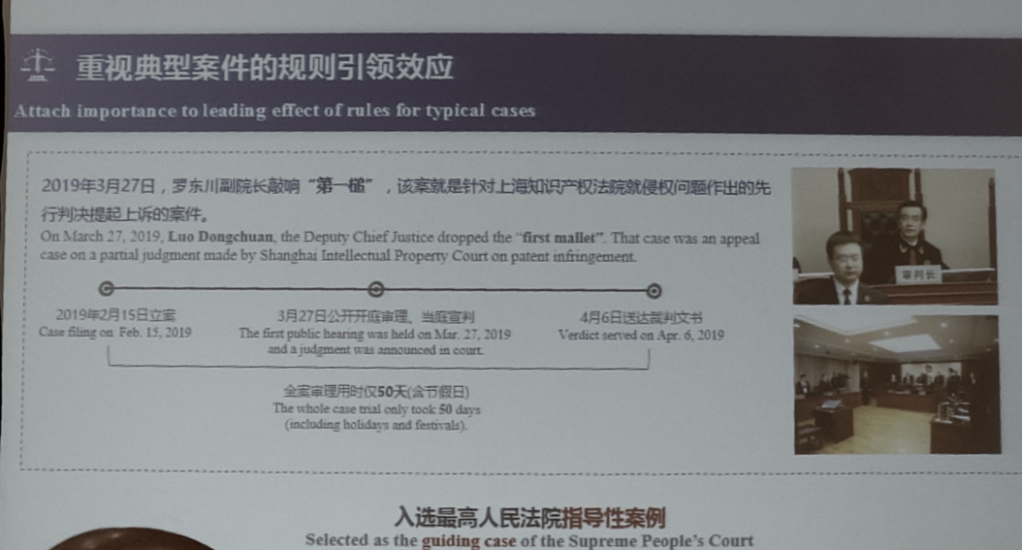

Last year, the SPC issued its Guiding Opinions on Strengthening Searches for Similar Cases to Unify the Application of Law (Provisional) (the “Opinion”) to regulate the practice of case adoption that may now apply to an ASI typical case. Susan Finder has aptly summarized the Opinion as “approving the practice of judges using principles derived from prior cases to fill in the gaps in legislation and judicial interpretations. The Opinion codifies many of the practices of the Chinese courts and imposes some new requirements. It does not mean that China has become a common law legal system… [C]omments by an SPC judge suggest that the special status of cases selected by the SPC by its operational divisions remains in place.” This strategy was also part of the original discussions in China about how to “roll out” ASI’s in China, as is evident from the above photograph that I took of a slide from a conference that focused on ASI’s in IP matters from January 2020 where the role of SPC-designated “guiding cases” was discussed..

The SPC’s recent efforts comes on the heels of leader Xi Jinping’s pathbreaking article in Qiushi on January 31, 2021. In that speech, Xi Jinping did not call for any significant changes to China’s notable experiments in creating IP courts and a national IP court for technology issues. Xi also noted that it “was necessary” to “promote the extraterritorial application of China’s laws and regulations” and for China to “build a system for preventing and controlling intellectual property foreign-related risks” as well as to “improve the adjudication of technical IP rights.” The speech was first delivered on November 30, 2020, three months after the Conversant decision by the SPC.

The first effort to identify an ASI case came in a report on the new SPC IP Court’s two-year work, in which the SPC listed 55 typical IP cases of the 2787 cases that it heard in 2020. The first case listed is the Huawei v. Conversant ASI case. According to this report, these cases were pathbreaking in two aspects: (a) their consideration of the factors for issuing an ASI; and (b) calculations of fines for disobeying an ASI. A translation of the ASI decisions in these three cases (2019 最高法知民终732, 733, 734 号) is available here. The factors are similar to those articulated by US courts, such as the US Unterwester or Gallo factors as well as general standards for a preliminary injunction, (In re Unterweser Reederei GMBH, 428 F.2d 888, 896 (5th Cir. 1970), aff’d on reh’g, 446 F.2d 907 (5th Cir. 1971) (en banc) (per curiam), rev’d on other grounds sub nom. M/S Bremen v. Zapata Off-Shore Co., 407 U.S. 1 (1972); E. & J. Gallo Winery v. Andina Licores S.A., 446 F.3d 984 (9th Cir. 2006), Here is a rough translation of the summary given of those factors:

“The factors identified are: whether the respondent’s application for the enforcement of the extraterritorial court judgment will materially affect the adjudication and enforcement of the Chinese litigation; whether it is necessary to undertake behavior preservation measures; whether the damages to the applicant of not undertaking behavior preservation measures will outweigh the damages to the respondent of taking such measures; whether taking behavior preservation measures will damage public interests; whether taking behavior preservation measures complies with international comity principles; and other factors that should be given due consideration.

Regarding whether the application for the enforcement of extraterritorial court’s judgment will materially affect the adjudication and enforcement of the Chinese litigation, considerations can be given to: whether the parties to the domestic litigation and the international litigation are fundamentally identical; whether the subject matters overlap; and whether the effects of enforcing the applicant’s extraterritorial court’s judgment will interfere with the Chinese litigation.

Regarding whether it is necessary to undertake behavior preservation measures, emphasis should be put on: investigating whether not taking behavior preservation measures will cause irreparable harm to the applicant’s legal rights and difficulties in enforcement of the case’s adjudication; and whether these harms include material tangible damages including business opportunities and market interests. etc.; damages to economic interests including damages to litigation interests; and damages to Chinese interests including damages to extraterritorial interests.

On the international comity principle, considerations can be given to: the order of acceptance of the cases: the appropriateness of exercising jurisdiction; and the effect to the extraterritorial court’s trial and judgment, etc.”

Here is the Chinese original:

被申请人申请执行域外法院判决对中国诉讼的审理和执行是否会产生实质影响;采取行为保全措施是否确属必要;不采取行为保全措施对申请人造成的损害是否超过采取行为保全措施对被申请人造成的损害;采取行为保全措施是否损害公共利益;采取行为保全措施是否符合国际礼让原则;其他应予考虑的因素。关于被申请人申请执行域外法院判决对中国诉讼的审理和执行是否会产生实质影响,可以考虑中外诉讼的当事人是否基本相同、审理对象是否存在重叠、被申请人的域外诉讼行为效果是否对中国诉讼造成干扰等。关于采取行为保全措施是否确属必要,应着重审查不采取行为保全措施是否会使申请人的合法权益受到难以弥补的损害或者造成案件裁决难以执行等损害;该损害既包括有形的物质损害,又包括商业机会、市场利益等无形损害;既包括经济利益损害,又包括诉讼利益损害;既包括在华利益损害,又包括域外利益损害。关于国际礼让原则,可以考虑案件受理时间先后、案件管辖适当与否、对域外法院审理和裁判的影响适度与否等。

Regarding the separate issue of the calculation of fines, the court approved calculations based on the number of days of violating the ASI, with fines accumulated for each day of the violation. On a separate point, I wonder if the high fines that are threatened will now set a new standard for fining parties in other IP-related proceedings. These fines could be extremely helpful in mandating compliance with the enhanced discovery provisions of recently amended Chinese IP laws and in other areas.

In another release, the SPC issued a list of 10 typical technology IP cases 技术类知识产权典型案例, which may also qualify as “similar cases” as set forth in the Opinion. The first case listed is also Huawei v. Conversant . The reasons for listing these 10 cases included their effective protection of national interests, judicial sovereignty, and the legal interests of enterprises. The Conversant decision is praised not only for its role in setting the factors for issuing an ASI and fine calculations, but also for its role in establishing a complete ASI system using the experience of that case.

In discussing the Conversant case, the SPC noted that after the initial decision to grant an ASI was made within 48 hours on Huawei’s ex parte request, Conversant’s arguments for reconsideration were rejected and a settlement was reached, with a “very good legal result and multiple wins for society.” To further underscore the point made in the introduction to all of the 10 cases and the consistency with Xi Jinping’s speech, the SPC repeated that the court “effectively protected national interests, judicial sovereignty and enterprises’ legal interests.”

I suspect that the “very good legal result” of this “typical case” may be in the eyes of the beholder. All judicial decisions should result in “very good legal results”, regardless of whether a foreigner or domestic party wins. Judicial commentary on the value of cases like these is potentially concerning and could be seen as encouraging litigation against foreigners. In another well-known prior incident, a Chinese judge similarly encouraged Chinese enterprises to use the Chinese domestic legal system as a leverage to “break through technical barriers” presented by SEP litigation overseas. Overall, these efforts are not unlike prior efforts by the IP judiciary to identify typical cases to demonstrate China’s “judicial sovereignty” in its dealing with US “extra-territorial” Sec. 337 disputes back in 2014.

I believe that these policy changes in ASI’s are not the only outcomes of Xi Jinping’s speech, and others may yet be implemented. Among the other changes to date, the call for improved quality of IP rights has already had a demonstrable impact on efforts of China’s patent office to improve patent quality. A recent judicial interpretation on punitive damages similarly has a long policy history, but is likely inspired by the requests of Xi Jinping to improve judicial deterrence.

This is not the first effort by the courts to create consistency in judicial decision making in SEP disputes. The Guangdong Trial Adjudication Guidance for Standard Essential Patent Dispute Cases (Experimental Implementation) was one such notable provincial-level effort, which were discussed here (the “Guangdong Guidance”). It appears that at a national level, there may remain other uncertainties in how to best adjudicate SEP disputes in a range of substantive and procedural areas. According to the database of the Stanford Guiding Cases Project, there is still no Guiding Case on FRAND-related issues. Only Guiding Cases that are formally designated should be cited by the courts. Even then, Guiding Cases are still inferior to the Law, Regulations and Judicial Interpretations, where guidance is even more limited. The Guangdong Guidance also remains both local and “experimental”. Considering the rapidly evolving political and legal dynamics in this area, it is not surprising that the courts remain cautious. They may be waiting until they obtain more experience in various aspects of these disputes.

Categories: 337, ASI, Cases, China IPR, Conversant, Dueling Cases, Foreign Related Cases, guiding cases, Model Cases, Precedent