How much will the IP Sections of the Phase 1 Agreement (the “Agreement”) with China change IP strategies in China? For the most part, the Agreement adds much less than its appearance might suggest. Many of the important changes that the Agreement memorializes have recently been codified into law or set into motion for forthcoming codification. There are some important prospective changes in the text, particularly regarding pharmaceutical patent protections and in civil and criminal enforcement. If these changes are well-implemented, that could augur significant changes in the future. Nonetheless, a cautious approach should be taken to these changes as well, as many of them have a long history of disappointing US rightsholders. An additional problem with the Agreement is its reliance on administrative mechanisms that have a track record of not providing sustained protection for IP rights.

The IP-related sections are found in Chapter 1 of the Agreement (“Intellectual Property”) and Chapter 2 (“Technology Transfer”). Chapter 1 is divided into the following sections: General Obligations, Trade Secrets and Confidential Information, Pharmaceutical-Related Intellectual Property, Patents, Piracy and Counterfeiting on E-Commerce Platforms, Geographical Indications, Manufacture and Export of Pirated and Counterfeit Goods, Bad-Faith Trademarks, Judicial Enforcement and Procedure in Intellectual Property Cases, and Bilateral Cooperation on Intellectual Property Protection. Chapter 2 concerns Technology Transfer and is not divided into separate sections.

There are many concerning textual aspects of the Agreement. For example, it is unclear why “Technology Transfer” was not considered an IP issue in the Agreement. Additional ambiguities are supplied by inconsistent use of legal language as well as differences in the English and Chinese texts, both of which are understood to be equally valid (Art. 8.6). A careful reading shows that in many cases the Agreement does not afford any new progress on particular issues, but merely serves as a placeholder on issues that have long been under active discussion (e.g., on post-filing supplementation of pharmaceutical data in patent applications). There are also several provisions that appear to break new ground, such as in consularization of court documents by foreigners and enforcement of civil judgments.

Reactions from the dozens of people I spoke with about the Agreement in the US and China have been mixed. One prominent Chinese attorney thought that Chinese IP enforcement officials were now much more likely to be responsive to US requests in forthcoming enforcement proceedings. Several individuals thought that the Agreement would be a great stimulus to IP agencies and the courts in their enforcement efforts as well as in drafting new laws, regulations and judicial interpretations. Many academics were perplexed by the unclear language in the Agreement. Some experts shared my view that the Agreement places an undue emphasis on the wrong issues, such as punitive damages, administrative campaigns, and criminal punishment at the expense of compensatory civil compensation. Due to the numerous errors and inconsistencies in the Agreement, many people speculated that the negotiators on the US side and/or the Chinese side may not have been adequately consulting with experts, bringing to mind the Chinese expression of “building a chariot while the door is closed (without consulting others)” (闭门造车). The administrative and Customs enforcement provisions were dismissed by many as out of date or just for show. On the other hand, it did appear that the Chinese negotiators did rely upon their interagency experts. Susan Finder, the author of the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) Monitor, told me that the SPC (and likely the Supreme People’s Procuratorate [SPP]) provided input to the Chinese negotiating team.

Review of the Individual Sections and Articles

The trade secret provisions generally memorialize amendments already made to China’s Anti-Unfair Competition Law, including an expanded scope of definition of “operator” (Art. 1.3), acts that constitute trade secret infringement (Art. 1.4), as well as a shifting of burden of proof in civil proceedings where there is a reasonable basis to conclude that a trade secret infringement has occurred (Art. 1.5). Interestingly, the United States asserts in this section that it provides treatment equivalent to such shifting of a burden of proof. I am unaware of any nationwide burden-shifting in US civil trade secret proceedings, except – as a stretch – insofar as US discovery proceedings provide an opportunity to compel production of evidence from an adverse party. This view was also shared by others I had spoken to.

The trade secret provisions also require China to provide for preliminary injunctions in trade secret cases where there is an “urgent situation”. The use of preliminary injunctions to address early-stage trade secret theft has long been under discussion between the US and China. This is an awkward hybrid of Chinese and English legal standards. Generally the test in Chinese law for “action preservation” as in US law for “preliminary injunctions” is whether there is irreparable injury arising from such urgent situation which necessitates provisional relief (See Sec. 101 of Civil Procedure Law) An “urgent” situation which is not likely to cause irreparable injury does not require granting of a preliminary injunction. China’s judicial practice currently permits the use of preliminary injunctions where there is a risk of disclosure of confidential information (关于审查知识产权纠纷行为保全案件适用法律若干问题的规定, Art. 6.1). It appears likely that the current test for preliminary injunctions are unaffected by this provision, and the provision just memorializes current Chinese law – notwithstanding that is unclear about the standards and scope of action preservation procedures in China

The Agreement also uses inconsistent nomenclature to describe preliminary injunctions. As noted, the Chinese text does not refer to preliminary injunctions but refers to an overlapping concept of “action preservation.” Other provisions of the English language text of the Agreement discuss “preliminary injunctions or equivalent effective provisional measures” (Art. 1-11).

Historically, Chinese judges have been highly reluctant to issue preliminary injunctions. As Susan Finder has noted in an email to me, the language in the Agreement also does not address the underlying structural problem that judges may be reluctant to give injunctions because they are concerned they will be found to have incorrectly issued them, and hence held accountable under the judicial responsibility system. The Agreement also does not account for the fact that provisional measures serve a different function in the Chinese system compared to the United States. China concludes its court cases far more quickly than the United States, thereby providing more immediate relief, often without needing recourse to provisional measures if there is not an urgent need.

The Agreement also requires China to change its trade secret thresholds for “initiating criminal enforcement.” (Art. 1.7). The Agreement does not specify what measures are to be reformed, such as the Criminal Law or Judicial Interpretations, or standards for initiating criminal investigations by public security organs and/or the procuracy and State Administration for Market Regulation (SAMR) administrative enforcement agencies (See, e.g., 关于公安机关管辖的刑事案件立案追诉标准的规定(二)). The issue of what constitutes “great loss” for calculating criminal thresholds has itself been the subject of discussion and changing standards over the years.

As mentioned in Susan Finder’s November 26, 2019, blogpost, a judicial interpretation on trade secrets is on the SPC’s judicial interpretation agenda for 2020, scheduled for issuance in the first half of the year. Additional guidance may be expected from the procuratorate, SAMR, and Ministry of Public Security to address criminal enforcement issues.

Consistent with the Foreign Investment Law, the Agreement also prohibits government authorities from disclosing confidential business information (Art. 1.9).

The Pharmaceutical-Related Intellectual Property section of the Agreement requires China to adopt a patent linkage system, much as was originally contemplated in the CFDA Bulletin 55, but subsequently did not appear in the proposed patent law revisions of late 2018. Linkage will be granted to an innovator on the basis that a (a) company has a confidential regulatory data package on file with China’s regulatory authorities, and (b) where a third party, such as a generic pharmaceutical company, seeks to rely upon safety and efficacy information of the innovator. The drafters seem to be describing a situation similar to an Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) in the United States under the US Hatch-Waxman regime. According to US procedures, a generic company needs to demonstrate, inter alia, bioequivalent safety and efficacy to an innovator’s pharmaceutical product in order to obtain regulatory approval. Notice is thereafter provided to the patent holder or its licensee of the application for regulatory approval to address the possibility that the generic company may be infringing the innovator’s patent(s).

This linkage regime, if properly implemented, with be an important step for Chian’s struggling innovative pharmaceutical sector. China’s proposed linkage regime also extends to biologics (Art 1.11). Taiwan has also recently introduced a linkage regime.

In order to implement the linkage regime, the Agreement requires an administrative or judicial process for an innovator to challenge a generic company’s market entry based on the generic company’s infringement of a patent held by the innovator As drafted, the Agreement omits a requirement to amend China’s patent law or civil procedure law to permit a court to act when there is an “artificial infringement” by reason of approval of an infringing product for regulatory approval, notwithstanding the lack of any infringing manufacturing, use or sale of the product prior to its introduction into commerce in China. The lack of a concept of “artificial infringement” could make it especially difficult to implement a civil linkage regime in China. The US Chamber of Commerce and the Beijing Intellectual Property Institute (BIPI) had previously recommended revising Article 11 of China’s patent law to address this issue. BIPI had noted in its report that “Lacking of artificial infringement provisions results in lacking [sic] of legal grounds for the brand drug company to safeguard their legal rights.” This provision likely reflects continuing turf battles between the courts and China’s administrative IP agencies in enforcing IP rights. Implementation of a linkage regime by China’s National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) may be possible in the alternative, as a matter of its regulation of pharmaceutical products, however, there may be concerns that NMPA lacks the necessary expertise and independence to properly adjudicate pharmaceutical patent disputes.

The Agreement also does not reference regulatory data protection, which was one of China’s WTO obligations, nor does it reference China’s efforts to adopt an ‘orange book’ similar to the US FDA’s to govern patent disclosures and regulatory data protection as recommended by CFDA Bulletin 55. This section also reiterates in general terms a commitment by China to provide for post-filing supplementation of data in pharmaceutical patent matters, which has been a long-standing request of the US reflected in several JCCT commitments. Permitting post-filing supplementation is necessary to support a linkage regime. In the absence of any meaningful patent grants, China’s patent linkage commitments would be a hollow outcome.

The Patent section continues the focus on pharmaceutical IP by providing for patent term extension due to regulatory delays for pharmaceutical patents, including patented methods of making and using pharmaceutical products (Art. 1.12). The draft patent law already provides for patent term extension. The additional encouragement is welcome.

There are no provisions in this Agreement addressing non-pharmaceutical patent concerns. Companies that may have concerns about such issues as: standards-essential patent prosecution or litigation, low-quality patents, patent trolls, procedures involving civil or administrative litigation involving patents or Customs enforcement of patents, China’s increasing interest in litigating global patent disputes for standards-essential patents, the relationship between industrial policy and patent grants, expanding the scope of design patent protection, China’s amending its plant variety protection regime and acceding to the most recent treaty obligations, etc., will find that their issues are not addressed.

Section E on “Piracy and Counterfeiting on E-Commerce Platforms” addresses “enforcement against e-commerce platforms”. By its terms, it does not specifically discuss e-tailers, online service providers or other third parties.

The text (Art. 1.13) seeks to clarify and update the E-Commerce Law by “eliminat[ing] liability for erroneous takedown notices submitted [presumably by rightsholders] in good faith,” extending mandating a time period of 20 days for rightsholders to file an administrative or judicial response to a counter-notification, and penalizing counter-notifications taken in bad faith. Joe Simone (SIPS) has told me this Article’s 20 day period may require an amendment to the E-Commerce law, which currently requires a 10 day period.

Article 1.14 specifically addresses infringement on “major” e-commerce platforms. As part of this commitment, China also agreed to revoke the operating licenses of e-commerce platforms that repeatedly fail to curb the sale of counterfeit and pirated goods. It is unclear from this text if this provision is limited to “major” platforms as the title suggests (in both English and Chinese), or to platforms of any size as the Article itself states. In addition, it is unclear what kind of “operating license” is involved auch as a general business license or a license to operate an internet business. Whatever license is involved, this remedy has theoretically been available for some time for companies that sell infringing goods. As I recall, past efforts to use license revocations to address IP infringement had little success. Smaller enterprises might be able to circumvent the license revocation, perhaps by transferring businesses to another platform In the past, companies also evaded enforcement obligations by establishing a new business incorporated or operated under their name or that of a relative or friend. This provision, similar to other IP provisions of the Agreement, rehashes earlier JCCT commitments with apparent disregard to lessons previously learned or developments in Chinese law and its economy.

Article 1.14 notes, unlike other Articles which note that the United States has equivalent procedures, tellingly states that the United States “is studying additional means to combat the sale of counterfeit or pirated goods.” According to news reports, the USTR has threatened to place Amazon on the list of “notorious markets.” Since the publication of the Agreement, Peter Navarro at the White House has also threatened to crack down on US platforms due to the increased pressure of the trade deal to “combat the prevalence of counterfeit or pirated goods on e-commerce platforms.”

The Geographical Indications (GI) Section (F) continues long-standing US engagement with China with respect to its GI system. The Agreement requires that multi-component terms that contain a generic term will not be protected as a GI, consistent with prior bilateral commitments. China will also share proposed lists of GI’s it exchanges with other trading partners with the US to help ensure that generic terms are not protected as GI’s. The competing GI systems of the United States and China have been the subject of decades of diplomacy. This Section arguably is intended primarily to show political support for American companies that manufacture or distribute generic food and other products that compete with GI-intensive products such as wine and cheese. It is also likely intended to support US advocacy around these issues at the WTO, WIPO and bilaterally.

Section G requires China to act against counterfeit pharmaceuticals and related products, including active pharmaceutical ingredients (API) and bulk chemicals (Art. 1.18). It is unclear if these APIs need to be counterfeited to be seized, or if they should be liable for seizure because they are low quality or contribute to the manufacturing of counterfeit goods. The issue of API’s and bulk chemicals contributing to the production of counterfeit medicine has long been a discussion point between the US and China and had been the subject of JCCT outcomes. Providing API’s to counterfeiters is already a crime and civil violation. It can also give rise to administrative liability, although administrative agencies have often not prioritized contributory liability. Thanks to Joe Simone again, for providing me with the benefit of his experiences in this area.

China is also required to act against “Counterfeit Goods with Health and Safety Risks” (Art. 1.19). The text does not explicitly address unsafe products that do not bear a counterfeit trademark or the enforcement agencies that will implement this commitment. Generally, the burden of enforcing against counterfeit products belongs to trademark enforcers, rather than enforcement officials involved in product quality or consumer protection violations. However, the NMPA and/or the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology are specifically named as enforcement agencies in a related provision to this one (Art. 1.18).

This section also seeks to address “Manufacture and Export” of these goods, including “block[ing]” their distribution (chapeau language). It does not elaborate on how such cross-border steps will be undertaken – such as by Customs agents, law enforcement authorities, cooperation between food and drug regulatory agencies, or through bilateral or multilateral law enforcement cooperation.

The failure to clearly designate a responsible agency in these administrative and law enforcement commitments can lead to problems with enforcing IP rights. The academic literature, including that of Prof. Martin Dimitrov, has suggested that when multiple agencies have unclear and overlapping IP enforcement authority, they may be more inclined to shirk responsibility. I hope that coordination mechanisms for these and other outcomes have been well-negotiated to address this issue.

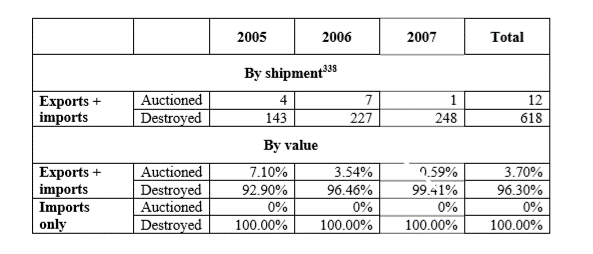

Article 1.20 addresses the destruction of counterfeit goods by Customs, in civil judicial proceedings and in criminal proceedings. Article 1-20(1) requires Customs to not permit the exportation of counterfeit or pirated goods Due to the growth of e-commerce and B2C exports from China via online platforms, container-sized seizures have become rarer, and the practical consequences of this provision may be limited. Moreover, rightsholders have not often complained of Customs’ destruction procedures. A WTO case brought by the United States involving Chinese customs destruction procedures also failed to identify losses to the United States by reason of China’s not disposing of seized goods outside of the channels of commerce consistent with its WTO obligations to seize goods on import (DS362) (see 0% auctioned on imports, below). At that time, when containerized shipment seizure was more common, only 3.7% of imported and exported goods were auctioned by value and 1.9% by shipments.

My former colleague, Tim Trainer, has identified what is new in the Agreement in Customs as seizures in transit.

The Article does not define what is a “counterfeit” good, or whether manufacturing a product for export may constitute an infringement of the rights of a third party that holds the right in China, which is the so-called OEM problem. In a typical OEM scenario, the importer in a foreign country owns the relevant rights in the importing country, but not in China.

Article 1.20(2)(d) requires the courts to order that a rightsholder be compensated for injury from infringement in civil judicial procedures, presumably when goods are seized. It is unclear to me why the Agreement does not address the critical issue of affording adequate civil damages generally, why it is limited to the Customs context, and why the Agreement does not generally address the overuse of low statutory damages in IP-related civil disputes generally.

The Agreement requires that materials and implements which are “predominantly” used in the creation of counterfeit and pirated goods shall be forfeited and destroyed. This “predominant use” test is derived from the TRIPS agreement. It regrettably provides a basis for goods that are demonstrated to have a less than dominant use (e.g., 49.9 percent) to avoid forfeiture and destruction. A better test might have been to encourage China to use a “substantial use” test, or a test based simply on use in commercial-scale counterfeiting and piracy. IP owners may wish to consider using judicial asset preservation measures by the courts in order to address issues involving the seizure of goods that are also used for legitimate manufacturing purposes.

Destruction of counterfeit goods by Market Supervision Bureaus in administrative trademark enforcement proceedings is not discussed in this Agreement and has been an area of concern by rightsholders in the past. This omission is concerning as China’s administrative enforcement of trademarks has historically been a highly active area of IP enforcement on behalf of foreign rightsholders.

Section H addresses the bad-faith registration of trademarks. No specific action is required by China in the text. I have previously discussed the importance of expanding concepts of “good faith” in IP protection in China with hopes that it would be addressed in resolving the trade war and had specifically noted two issues addressed in the Agreement: bad-faith registration of trademarks, and ensuring that employees were covered objects of China’s trade secret law. Certain steps have already been undertaken by relevant agencies to address the important issue of bad faith trademark registrations, including: supporting oppositions/invalidation against marks filed in bad faith and with no intention to use (Article 4 of the Trademark Law); addressing the problem of trademark agencies that knowingly facilitate those bad faith trademark filings under Article 4, and imposing administrative fines against bad faith trademark applicants for a purpose other than use or judicial punishments against pirates that bring trademark infringement lawsuits against brand owners victimized by bad-faith registrations.

Given the lack of identified concrete next steps in this important area, China may not be planning to do little more legislation in this area in the near future, and/or waiting to better evaluate the impact of recently implemented measures and policies, including provisions allowing fines to be imposed against trademark pirates. Joe Simone has suggested that one helpful measure to consider in the future might be for courts to award compensation for legal and investigation fees in bad faith cases, ideally by the same courts handling invalidation and opposition appeals.

Section I requires the transfer of cases from administrative authorities to “criminal authorities” when there is a “reasonable suspicion based on articulable facts” that a criminal violation has occurred. “Criminal authorities” are not defined. This could include the Ministry of Public Security and/or the Procuracy. The intent behind this provision is likely to ensure more deterrent penalties for IP violations and avoid the use of administrative penalties as a safe harbor to insulate against criminal enforcement. This problem of low administrative referrals is an old and thorny one. In bilateral discussions of the last decade, we would often inquire about the “administrative referral rate” of China, which is the percentage of administrative IP cases that were referred to criminal prosecution, which has historically been quite low. See National Trade Estimates Report (2009) at pp. 101-102. However, if administrative agencies are required to transfer cases to the Public Security Bureau or Procuratorate, it will have little impact unless these agencies accept the case and initiate prosecutions. A loophole in this text may be that it does not mandate that a case is accepted after it has been referred by administrative agencies, thereby risking non-action by prosecutors. As administrative agencies have more limited investigative powers, the evidence provided by administrative authorities may also often be insufficient to initiate a criminal investigation.

Article 1.27 requires China to establish civil remedies and criminal penalties to “deter” future intellectual property theft or infringements. These requirements are also found in the TRIPS Agreement. The English language text of the Agreement conflates the role of civil remedies and criminal penalties and their deterrent impact. Civil remedies should, at a minimum, deter or stop (制止,阻止) the defendant from repeating the infringing act, whereas criminal remedies might also provide broader social deterrence (威慑 as in nuclear “deterrence”, which is found in the Chinese version of the Agreement). This paragraph and the Agreement more generally do not underscore the important role of compensatory civil damages in providing deterrence.

The Agreement also requires China to impose penalties at or near the maximum when a range of penalties is provided and to increase penalties over time.

These provisions regarding criminal enforcement generally reflect concerns articulated in the unsuccessful WTO IP case the US brought against China to lower its trademark and copyright criminal thresholds (DS362). However, the lost lesson from that case is that criminal thresholds are not as important as other factors in creating deterrence. Prosecutors may still decline in fact to prosecute cases, even if they are required by law to accept cases. Law enforcement may also lack adequate resources. Judges may also have discretion in imposing sentences. The calculation of the thresholds themselves, whether based on illegal income or harm caused, may be difficult to assess. The civil system also needs to play a robust role in creating respect for IP. The proof of the limited impact of lowering criminal thresholds is that criminal IP cases significantly increased in China after it lost the WTO case. After the United States “lost” that WTO case, the number of criminal IPR cases rapidly increased to a high of approximately 13,000 in 2013. Whether the Chinese data of 2013 was calculated to include only IPR-specific crimes or crimes that may encompass IPR-infringing products (such as involving substandard products), this was a dramatic increase from approximately 2,684 criminal IP cases or 907 IPR infringement crimes from 2007. The bottom line is that simply increasing criminal cases through lower thresholds may not be enough to create a healthy IP environment.

Another issue of concern is that foreigners have often been named as defendants in serious civil or criminal cases. The first significant criminal copyright case in China involved American defendants distributing counterfeit DVD’s. More recently, patent preliminary injunction cases were granted in favor of two different Chinese entities in two cases against American defendants (Micron and Veeco). The largest patent damages case involved the first instance decision in Chint v. Schneider Electric (330 million RMB). The NDRC investigation of Qualcomm similarly pioneered high antitrust damages in an IP licensing matter. In many instances, the final decisions in pioneering cases where foreigners lost were also never published. Given this track record, we might not want to be advocating for harsher enforcement in the absence of greater commitments to due process and transparency.

The Agreement also pioneers by providing for expeditious enforcement of judgments (Article 1.28). According to Susan Finder, the SPC already lists judgment debtors in its database. This is a welcome area of engagement and should also be supported by continuing transparency in this area.

Over the past several years, there has been an increasing incidence of multijurisdictional IP disputes, particularly in technology sectors. The Agreement does not address the problems arising from these cases. It does not mention that China does not enforce US judgments, although the US has begun enforcing some Chinese money judgments, nor does it address the practice of many Chinese courts to fast track their decision making to undercut US cases. Generally, US lawyers cannot conduct discovery in China and formal international procedures to collect evidence are slow. Both Chinese and US courts often rarely apply foreign law, even when such law may be more appropriate to resolution of a dispute. Based on a recent program I attended at Renmin University, it also appears likely that Chinese courts will issue their own anti-suit injunctions soon. The Agreement also does not require anything further in terms of judicial assistance in gathering evidence. These are areas for potential cooperation as well as confrontation. Indeed Berkeley and Tsinghua have held a continuing series of conferences on this topic. At the recent Renmin University conference, British, German, US and Chinese judges exchanged their views on these topics in a cordial and productive manner. It is my hope that this topic is an area of collaboration, not confrontation.

Regarding copyright, Article 1.29 provides for a presumption of ownership in copyright cases and requires the accused infringer to demonstrate that its use of a work protected by copyright is authorized. It would also have been helpful if the US and China had discussed the problem of title by title lawsuits in China, which has also increased costs of litigation through requiring multiple non-consolidated lawsuits for one collection of songs, photos or other works. One Chinese academic confided in me that the current practice of requiring that each individual title be the subject of an individual lawsuit was not the original practice in China’s courts and that the old practice was more efficient for both the courts and rightsholders.

The Chinese and English texts of the Agreement also differ to the extent that the English text refers to the US system of related rights, while the Chinese next refers to the Chinese (and European system) of neighboring rights.

In terms of civil procedure, Article 1.30 permits the parties to introduce evidence through stipulation or witness testimony under penalty of perjury, as well as requiring streamlined notarization procedures for other evidence. China’s ability to implement “penalty of perjury” submissions is limited by China generally lacking a concept of authenticating a document under penalty of perjury, which also hampers lawyer’s ability to represent clients by powers of attorney. The implementation and impact of this provision is unclear.

Article 1.31 permits expert witness testimony. Expert witnesses are already permitted under existing Chinese law, although the trend appears to favor greater use of them. Moreover, Chinese courts have been expanding the role of expert technology assessors to provide support for technologically complex cases. Once again the implementation and impact of this provision is uncertain, although we can expect further developments from the courts in this area, particularly in anticipated guidance concerning evidence in IP cases.

Article 1.35 requires that China adopt an action plan to implement the IP chapter of the Agreement. In an additional welcome development, the Agreement also supports reinstatement of cooperative relationships with the USPTO, the USDOJ and US Customs.

Chapter 2 addresses US allegations regarding forced technology transfer. It prohibits China from seeking technology transfer overseas consistent with its industrial plans subject to the qualifier that such plans “create distortion.” Distortion is not defined.

Other provisions prohibit require technology transfer as a condition of market access, using administration or licensing requirements to compel technology transfer and maintaining the confidentiality of sensitive technical information. These are consistent with the recently enacted Foreign Investment Law and other legislation.

The Technology Transfer provisions do not address whether the provisions that were removed from the TIER are now governed by China’s Contract Law and proposed Civil Code provisions on technology transfer contracts. Clarity on this important issue could help support the autonomy of parties to freely negotiate ownership of improvements and indemnities. The Agreement also does not address the regulation of licensing agreements by antitrust authorities or under China’s contract law or proposed civil code for the “monopolization” of technology. The Civil Code provisions are now pending before the NPC and could have appropriately been raised as “low hanging fruit” in this Agreement. Antitrust concerns in IP had also been raised by several parties in the 301 report concerning IP concerns (at pp. 180-181). Hopefully, these issues will be decided in the Phase 2 Agreement.

Some additional hope for IP commercialization is afforded by the commitments by China in the Agreement to increase its purchases of services by $37.9 billion from the United States during the next two years, which include purchases of IP rights as well as business travel and tourism, financial services and insurance, other services and cloud and related services. Considering the central role played by forced technology transfer in this trade war, it was to be hoped that a specific commitment on purchases of IP rights might have been secured.

Concluding Observations

It is often difficult to discern the problems that the Agreement purports to address and/or the appropriateness of the proposed solution(s). In some instances, it also appears that USTR dusted off old requests to address long-standing concerns that may also not have high value due to technological and economic changes. For example, it is unclear to me if commitments in the Agreement regarding end-user piracy (Art. 1.23) by the government are as necessary today when software is often delivered as an online cloud-based service and not as a commodity. The leading software trade association’s position in the 301 investigation did not mention end-user piracy as a top-four priority (p. 4). Moreover, China had already been conducting software audits for several years and piracy rates had been declining. The commercial value of these commitments is also uncertain under China’s recent “3-5-2 Directive”, where the Chinese government is obligated to replaced foreign software and IT products completely with domestic products within the next three years. The Agreement already contains commitments for China to increase its share of cloud-based services. The issue does have a long and sad history. The U.S. Government Accountability Office had calculated 22 different commitments on software piracy in bilateral JCCT and economic dialogues between 2004 and February 2014.

Among the more anachronous provisions of the Agreement are the five separate special administrative IP campaigns that the Agreement mandates. The general consensus from a range of disciplines and enforcement areas (e.g., IP, counterfeit tobacco products, pollution, and taxation) that campaigns result in “short term improvements, but no lasting change.” Moreover, the focus of these campaigns, including Customs enforcement and physical markets appears outdated due to the growth of e-commerce platforms.

The situation was predictable: “late-term administrations may … be tempted to condone campaign-style IP enforcement, which can generate impressive enforcement statistics but have limited deterrence or long-term sustainability.” The Administration took this one step further, with enforcement campaign reports timed to be released during the various stages of the Presidential campaign. Here are some of the administrative campaign reports we can expect, with some corresponding milestones in the Presidential campaign season:

March 15: China is required to publish an Action Plan to strengthen IP protection and to report on measures taken to implement the Agreement and dates that new measures will go into effect. (Art. 1.35)

May 15: China is required to substantially increase its border and physical market enforcement actions and report on activities by Customs authorities within three months (or by April 15, 2020) (Art. 1.21).

May 15: China is required to report on enforcement activities against counterfeit goods that pose health or safety risks within four months and quarterly thereafter (Art. 1.19).

June 15: China is required to report on enforcement at physical markets within four months and quarterly thereafter (Art. 1.22). This report will coincidentally be released at the same time as the Democratic Party Convention.

August 15: China is required to report on counterfeit medicine enforcement activity in six months and annually thereafter (Art.. 1.18). This report will coincidentally be released approximately one week before the Republican Convention.

September 15: China is required to report on third party independent audits on the use of licensed software within seven months, and annually thereafter (Art. 1.23).

Also, a quarterly report is required regarding the enforcement of IP judgments (Art. 1.28).

There is no explanation provided in the Agreement for the timing of each of these reports, their sequential staging or why the usual date for release of government IP reports (April 26) is not being used.

There are many other important IP areas not addressed in the Agreement. The Agreement offered a missed opportunity to support judicial reform, including China’s new national appellate IP court, the new internet courts as well as local specialized IP courts at the intermediate level. The Agreement also entails no obligations to publish more trade secret cases, to make court dockets more available to the public, and to generally improve transparency in administrative or court cases, which might have made the Agreement more self-enforcing. Due to the relatively small number of civil and criminal trade secret cases and recent legislative reforms, the greater publication of cases would be very helpful in assessing the challenges in litigating this area and China’s compliance with the Agreement. The new appellate IP Court will be especially critical to the effective implementation of the important changes in China’s trade secret law as well as the implementation of the patent linkage regime. The patent linkage provision also similarly neglects to describe the critical role of the courts in an effective linkage regime. The Agreement to a certain extent memorializes the ongoing tensions between administrative and civil enforcement in China and regrettably reemphasizes the role of the administrative agencies in managing IP through campaigns and punishment.

The trade war afforded a once in a lifetime opportunity to push for market mechanisms in managing IP assets through a reduced role for administrative agencies and improved civil remedies in China’s IP enforcement regime. A high cost was paid in tariffs to help resolve a problem that the Administration estimated, or exaggerated, to be as high as 600 billion dollars. The reforms in the Agreement hardly total up to addressing a problem of that magnitude, and in many cases appear more focused on yesterday’s problems. While the continued emphasis on administrative agencies and limited focus on civil remedies is disappointing, there are nonetheless many notable IP reforms in the Agreement in addition to legislative reforms already delivered. I hope that a Phase 2 agreement will deliver additional positive changes that also address the challenges of the future

Please send me your insights, comments, criticisms or corrections! Happy Spring Festival!

Please send in any comments or corrections!

Revised 1/23/2020, 1/27/2020

Categories: Administrative enforcement, AML, BIPI, China IPR, civil code, Civil Enforcement, Customs, Data Supplementation, empirical research, Faux Amis: China-US Administrative Enforcement Comparison, FTT, JCCT, patent linkage, patent term extension, Pharmaceutical Patents, Phase 1 Agreement, Regulatory Data Protection, Software Asset Management, Software Piracy, Specialized IP Courts, TIER, Tim Trainer, Trade, Trade Secret, Trade Secrets, trade war, trademark squatting, Translation

Dear professor,

I am afraid my email below was sent to you by mistake, and I see it has now been published as a comment. Could you please delete the comment on your website?

Thank you very much.

Congratulations on the great article.

Kind regards

Stefaan

________________________________

Van: Meuwissen, Stefaan

Verzonden: dinsdag 4 februari 2020 21:45

Aan: ‘China IPR – Intellectual Property Developments in China’

Onderwerp: RE: [New post] The Phase 1 IP Agreement: Its Fans and Discontents

China-based in-house counsel at foreign companies in the pharmaceutical and consumer goods sectors, as well as academics, range from being cautiously optimistic to extremely hopeful about the phase one agreement of the US-China trade deal.

What is clear from our conversations, though, is the uncertainty on how exactly the measures in the agreement will be implemented. Depending on the details of these plans, there could be very different execution and enforcement efforts in future.

Pharma a big winner

On the pharmaceutical front, a number of measures that have been under active discussion are now included, but in-house counsel want to see more details of the plans before they get too excited.

According to the head of IP at a global pharmaceutical company, the ability to use supplementary data in patent applications, as prescribed in the agreement, will give more predictability to business planning.

“A lot of patents have been invalidated for lack of inventiveness in China,” he says. “Being able to establish inventiveness through supplementary data in legal proceedings will have a huge and immediate impact for the pharmaceutical industry.”

The head of IP continues: “The inability to use supplementary data has been harsh and draconian in China. It’s something that’s allowed in the US and Europe.”

In terms of IP strategy, being able to use such data is a dramatic turn. The in-house counsel of another pharmaceutical company says that patents will be less likely to be invalidated. “From a research and development context, it means that the creative research that goes into product development can now be presented on inventiveness grounds,” he says.

An area that has led to some confusion is the use of patent term adjustments versus patent term extensions in the agreement. Patent term adjustments refer to the days that can be recovered as a result of time lost during patent prosecution for delays that are not caused by the patentee. On the other hand, patent term extensions cover the time that can be added back to a patent as a result of the time lost from doing clinical trials.

“The language of patent term adjustments hasn’t been prevalent in China,” says the in-house counsel of the pharmaceutical company. “These need to be differentiated from patent term extensions.”

Additionally, he hopes to see more clarity around what types of patents will be included for patent term extensions and whether patents that existed before the phase one agreement was signed (in January) will be included.

Patent linkage clarity

But the one thing that in-house counsel are anticipating the most is what the patent linkage system outlined in the agreement will look like for China.

The in-house counsel at the pharmaceutical company wants to see more clarity in what the system will be like in practice.

“For instance, in terms of judicial practice, how long will it take to for the drug regulator to make a decision for patentees to make an appeal to the IP court?” he asks. “Mapping the system out with more certainty will enable us to do better business planning, such as knowing when to bring a drug to China and how long we can sell it for.”

It’s unclear whether China will develop a model similar to the patent linkage system in the US, where, for example, the first company to submit an abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) for a generic drug can get the exclusive right to market it for 180 days. A 30-month stay of the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of an ANDA application may be available if the patentee files a suit within 45 days of receiving a notice letter challenging one or more patents in the FDA’s Orange Book. Whether China’s system will be similar remains to be seen.

An interesting point that academics and IP counsel want more clarity on is what happens when it is necessary for innovator drug companies to litigate before a generic drug is marketed.

“The agreement requires an administrative or judicial process for an innovator to challenge a generic company’s market entry based on the generic’s infringement of a patent held by the innovator,” says Mark Cohen, director and senior fellow at the Berkeley Center for Law and Technology in California.

“But it omits a requirement to amend China’s patent law or civil procedure law to permit a court to act when there is an artificial infringement by reason of approval of an infringing product for regulatory approval, notwithstanding the lack of any infringing manufacturing, use or sale of the product prior to its introduction into commerce in China.”

He adds that the lack of an artificial infringement concept could make it difficult to implement a civil linkage regime in China. This provision probably reflects continuing turf battles between the courts and China’s administrative IP agencies in enforcing IP rights, he says.

Tech transfer trends

A trend to watch relating to the pharmaceutical sector and technology transfer is the amount of sensitive information involved with doing clinical trials in China and what will happen under the technology transfer provisions in the phase one agreement.

“In the past, there have been instances where government officials have disclosed sensitive data to local businesses either inadvertently or out of goodwill,” say the head of IP at the pharmaceutical company.

He continues: “Although it’s not an outright transfer of technology, what we have observed in the past for trials involving human genetic resources at local hospitals is that drug companies would be requested to share patient data in order for partnerships with hospitals to continue.”

He says he is curious about whether the provisions in the phase one agreement will hold up and whether the risk of being required to share data will continue.

Beyond pharma

Topics yet to be discussed are patent-related issues beyond the pharmaceutical industry. According to Cohen, the agreement hasn’t addressed a number of important IP concerns of businesses. These include: standard essential patents, low-quality patents, patent trolls, and civil and administrative patent litigation procedures.

From a brand protection perspective, the trademark counsel of a US consumer goods company says that the agreement’s focus on bad-faith marks helps to solidify the progress that has been made in China in the past year, including changes to the trademark law that became effective on November 1 2019.

However, an area that continues to cause headaches for her is the challenge with getting notarised evidence in counterfeiting cases, especially with the rampant rise of e-commerce sites in China.

When it comes to enforcement, she notes the reference to civil and criminal penalties to deter future IP theft or infringements. However, she wants to see more details before being too optimistic.

The counsel adds: “Although the criminal threshold for establishing trade secret cases has been eliminated, there is no similar measure for trademark cases.”

While the phase one agreement is a very positive first step and builds on the tremendous progress that China has made in IP protection, especially in the past year, in-house counsel want to see the action plan – which is expected to come out in February – to address the various measures in the agreement in more detail.

LikeLike